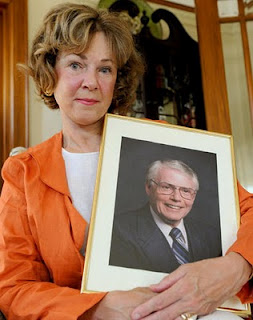

Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center has lost yet another formally adjudicated futility dispute. In 2008, Douglas DeGuerre was a patient at Sunnybrook

DeGuerre's daughter, Joy Wawrzyniak, brought several actions against providers there in several forums. I have blogged about some of those before. In the past few days, Wawrzyniak has finally achieved some measure of success. The Health Professions Appeals and Review Board has reversed and remanded a 2010 decision of the Inquiries, Complaints and Reports Committee of the College of Physicians

In 2008, Dr. C. (Martin Chapman) wrote a DNR order without DeGuerre’s or his surrogate’s consultation or permission. Dr. L. (Donald Livingstone) cosigned that order. Apparently, the surrogate (Wawrzyniak) had requested full code. But Dr. C. determined that it was an error to note “full code” on this patient’s chart. So, he reinstated the DNR order. Dr. C. had intended to discuss this with the surrogate. But the patient’s condition deteriorated more quickly than expected – “events overtook our usual processes of communication.”

In 2010, the Inquiries, Complaints and Reports Committee of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario determined that DNR was appropriate and that resuscitative measures would have been futile and not in the patient’s best interest. The Committee determined that the surrogate was in no position to demand treatment that physicians did not think medically appropriate. The Committee decided to take no action against Dr. C. and Dr. L.

In late January 2012, the Health Professions Appeals and Review Board reversed the Committee. While noting the deferential standard under which it reviews Committee decisions, the Board determined that the Committee failed to consider the Ontario HCCA requirement of patient consent for “treatment.” The patient had been offered a plan of treatment that included full code status. The surrogate accepted that plan. Therefore, arguably, any change to that treatment, the HCCA requires surrogate consent -- even it becomes increasingly obvious that the initially offered treatment is no longer beneficial or medically indicated. If, as in this case, the surrogate refuses to consent to a new treatment plan based on the patient’s developing condition, the HCCA appears to require that providers take the case to the CCB.

The Board determined that the Committee should have addressed whether it was really the standard of practice to make an incapacitated patient DNR without consent from the surrogate. Specifically, the Board held that the Committee should not have answered this question without considering provider obligations under the HCCA.

Since the meaning and legitimacy of these HCCA provisions are questions now pending before the Supreme Court of Canada in Rasouli, the Committee may want to wait for that decision before issuing a new decision against Dr. C. and Dr. L.

No comments:

Post a Comment